This is not one of those, “go-out-and-buy-some-test-equipment-and-try-this-at-home-type-blogs.”

Phantom Voltage or “induced voltage” is the result of wire or other metal components appearing to be energized when they in fact are not. How this works is that when you have ungrounded wiring, like Knob & Tube wiring or older ungrounded romex-type wiring in your home and you add metallic pathways (wires and conduit) to these old circuits the metal wires and/or conduit will pick up an induced voltage merely by being in proximity to the hot conductor in the circuit. The ungrounded wire and conduit–and anything attached to it that is not grounded will also appear “energized” (hot) by the simple little Voltage Indicator Tool that is in every home inspector’s tool kit.

Phantom Voltage can make the metal sides of refrigerators, metal light fixtures, metal surface conduit, and metal junction boxes appear energized. As an inspector, it might be my first clue that someone has added newer grounded wiring to the old ungrounded system. With the ground wire not connected to an actual ground source the voltage is induced into the unused ground wire–and just like magic we get Phantom Voltage. It would be important for the inspector to verify that this Phantom Voltage is not “real voltage” with potential because then there could be a serious shock hazard present. Otherwise, Phantom Voltage represents no real danger that I am aware of.

Sometimes homes have grounded-type wires run throughout the home, but the ground wire, for one reason or another, is either not connected to the devices (receptacles, switches, light fixtures etc), or the wire just simply isn’t being used–or even possibly disconnected somewhere.

Homes wired in the early 60’s often have this condition.

It was the early 60’s when we first started manufacturing house wiring that included a ground wire. Because there was no requirement to actually “use” the wire, these houses mimicked older houses with ungrounded wiring.

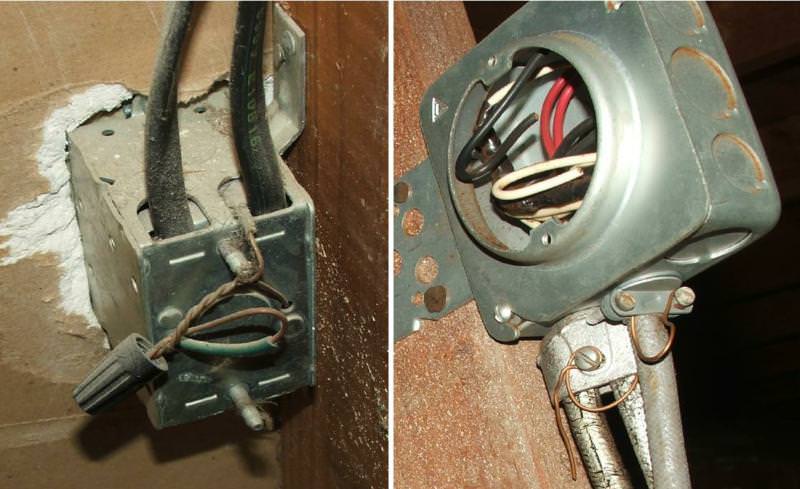

One can see these ground wires just run back out through the back of the boxes, where they are either twisted together and wire-nutted together, or they are merely cut off. Sometimes they were attached to the metal boxes sometimes they were not. We might see these boxes in unfinished basements or other partially finished areas of the home. Here are a couple of examples.

This becomes a problem for the inspector because it is difficult to check for reversed polarity of two-prong receptacles when the home has been wired this way. Both slots will read hot when approached by a “tick-tester/voltage indicator. In fact the entire area around the receptacle within 6″-8” of the receptacle might read “hot” with a voltage tester–we call this “Phantom Voltage” or “Induced Voltage.”

This Phantom Voltage is high enough to set off a 90-volt “tick-tracer” (voltage indicator). The voltage will actually be the same as whatever the voltage of the circuit is. Because it is an induced voltage, there is no actual amperage present so shocks are not an issue. For the inspector, “CONFUSION” is the issue, because of how all this induced current prevents testing of the device for polarity.

Of course it is critical for the inspector to determine whether this is actually phantom voltage or in fact actual current in the wrong place.

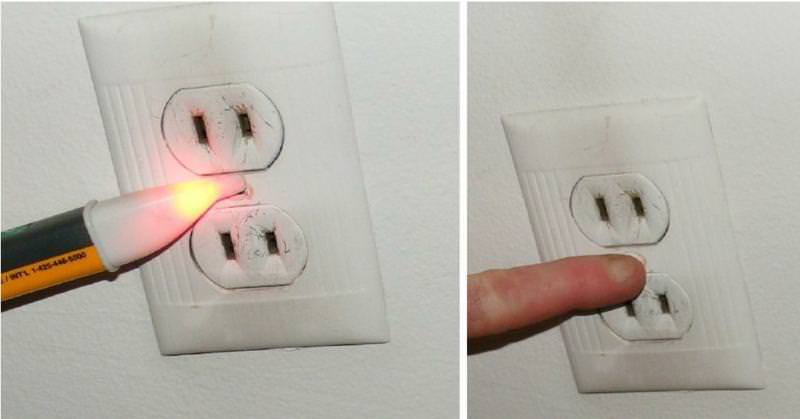

The following pictures demonstrate how the many parts of the receptacle and the surrounding wall test as “hot” with the voltage indicator.

Note that in the next picture, on the left, even the metal screw that holds the cover plate in place reads as “hot.” Simply touching the metal screw with one’s finger is enough to “cancel” the Phantom voltage allowing the inspector to use the tester normally to check for proper polarity of the receptacle.

xxx

Charles Buell, Seattle Home Inspector

If you enjoyed this post, and would like to get notices of new posts to my blog, please subscribe via email in the little box to the right. I promise NO spamming of your email